Fooled By Randomness

By Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Introduction

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a renowned scholar, philosopher, and former trader, widely known for his groundbreaking work on risk, probability, and uncertainty. With a career that spans financial markets, mathematics, and philosophical inquiry, Taleb has developed a unique perspective on randomness and its often underestimated role in human life and the financial world. As a practitioner, Taleb made a name for himself by profiting from extreme, unpredictable events, which he terms "Black Swans." His insights are usually contrary to the consensus, urging readers to embrace uncertainty and recognize the limits of human knowledge. Taleb’s works, including Fooled by Randomness, The Black Swan, and Antifragile, are celebrated for their deep philosophical reflections, practical wisdom, and sharp critiques of traditional risk models. Today, Taleb's ideas have become essential reading for investors, scholars, and anyone interested in navigating an increasingly unpredictable world.

Praise for the Book

Howard Marks, Co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management: “Taleb's work is essential for anyone who wishes to understand the nature of risk and uncertainty.”

Robert Shiller, Nobel Laureate in Economics: “Taleb illustrates the hidden influence of randomness on success and failure in a way that fundamentally alters our view of the world.”

Daniel Kahneman, Author of Thinking, Fast and Slow: “A brilliant reminder of the power of chance in everything we do.”

Key Takeaways

Here are some of the fundamental lessons from Fooled by Randomness:

The Role of Randomness: Taleb emphasizes that randomness, rather than skill, often plays a significant role in the outcomes we observe, especially in financial markets.

Expected Value: Taleb explains the critical importance of asymmetry in risk and reward. High-probability events do not always lead to success if the consequences of rare events are large enough.

Survivorship Bias: We often overestimate the skill of survivors in competitive environments because we fail to account for the numerous failures that are not visible.

Hindsight Bias: Taleb demonstrates how hindsight bias makes us believe events were predictable, even when they were not, leading to false confidence.

Noise vs. Signal: Taleb urges investors to differentiate between short-term noise and long-term signals when making decisions.

Black Swan Events: Taleb introduces the concept of Black Swan events—highly impactful, rare occurrences that are systematically underpriced by financial markets.

Risk and Asymmetry: Taleb stresses the importance of thinking probabilistically and considering asymmetric risks, where the magnitude of loss can overwhelm frequent small gains.

The Law of Large Numbers: He reminds readers that while results tend to average out over time, short-term variance can create misleading trends.

1. The Role of Randomness: Misunderstanding Luck and Skill

In Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb begins by highlighting the pervasive role of randomness in life, particularly in financial markets. He stresses how we tend to misattribute success and failure to skill or effort when, in reality, chance plays a much more significant role. This is especially true in fields like trading and investing, where outcomes are often influenced by market fluctuations beyond an individual’s control.

For example, a trader may have a string of profitable years, and they (or others) may believe it reflects their superior skill. However, Taleb cautions us to recognize the role of randomness in this success. The trader might have simply been in the right place at the right time, and their results could just as easily have been the product of favorable market conditions, not a reflection of skill. Over time, randomness tends to average out, which means that streaks of success (or failure) may simply be a product of variance and not necessarily a demonstration of talent. Taleb warns against taking short-term success as evidence of skill, as it could be just luck.

2. Understanding Expected Value: Why Probabilities Alone Aren't Enough

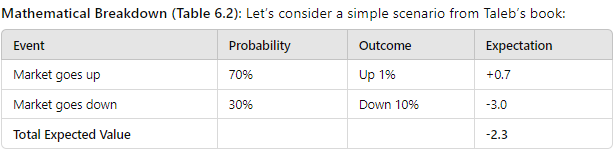

A key mathematical concept Taleb addresses is expected value. In finance, and particularly in trading, it’s not just about how often you win but how much you win or lose when you’re right or wrong. This introduces the idea that asymmetry in outcomes is far more important than probabilities alone.

In this case, we expect the market to rise 70% of the time, but only by 1%. When the market drops, it does so by 10%, even though the probability of this event is just 30%. The key takeaway here is that the expected value of this situation is negative: (+0.7)+(−3.0)=−2.3(+0.7) + (-3.0) = -2.3(+0.7)+(−3.0)=−2.3.

Even though you’re right most of the time (70% probability of gain), the rare 30% chance of a 10% loss dominates the overall outcome. The asymmetry between small gains and large losses means that the overall result can still be negative despite a high win rate. This concept is essential for understanding risk in financial markets, where large losses can outweigh frequent small wins. It’s a direct critique of many traders who focus only on win rates and ignore the severity of potential losses.

3. Survivorship Bias: Seeing Only the Winners

Survivorship bias is another central theme in Taleb’s philosophy. He explains that we often focus only on the survivors—the traders, companies, or fund managers who have done well—while ignoring the vast majority who have failed and disappeared from view. This creates a distorted perception of skill.

Example: Imagine 1,000 traders start their careers at the same time. Over 10 years, 900 of them fail and quit, while 100 succeed. If we only look at the surviving 100, we might assume they must have some special skill. In reality, many of them were likely just lucky. Taleb argues that success in these cases often has more to do with randomness than with talent.

The bias lies in focusing only on those who remain visible—the winners—and forgetting the failures who are no longer part of the sample. This is particularly dangerous in finance, where many fund managers with long track records may simply be the "lucky survivors" of a system filled with randomness. Taleb reminds us that this misperception can lead to overconfidence in attributing success to skill when, in fact, luck played a significant role.

4. Hindsight Bias: "I Knew It All Along" Fallacy

Hindsight bias refers to the tendency to believe, after an event has occurred, that the outcome was predictable all along. Taleb highlights how this bias distorts our perception of risk and randomness.

Example: Consider the financial crises of 2008 or the collapse of Archegos Capital (and the Investment Banks such as Credit Suisse that were wiped out because of holding margin accounts for Archegos) recently. After these events, many analysts and commentators retroactively claimed that the warning signs were clear. However, very few actually predicted these events with accuracy before they happened. Hindsight bias leads us to believe that these crises were foreseeable when, in reality, they were rare and unpredictable—Black Swan events.

Taleb cautions that relying on hindsight to make future predictions is a flawed approach. Instead of focusing on past outcomes, which can seem obvious after the fact, we should recognize that the future is inherently uncertain, and rare, impactful events can—and will—occur without warning.

5. Noise vs. Signal: Filtering Out the Irrelevant

Taleb places great emphasis on the distinction between noise and signal. In financial markets, most of what we hear—daily news, minor price fluctuations, even economic reports—is noise: irrelevant, distracting information that has little impact on long-term outcomes.

Example: Taleb critiques the obsession with daily financial news, particularly outlets like Bloomberg, which provide a constant stream of information that often leads to overreaction. He likens financial news to entertainment, arguing that most of it doesn’t matter in the grand scheme of things. Traders who react to every piece of news end up overtrading, making decisions based on noise rather than focusing on the underlying signal, or meaningful information.

The challenge is that separating noise from signal is incredibly difficult. Taleb advocates for focusing on fundamentals and long-term strategies, rather than reacting impulsively to every piece of short-term information.

6. Black Swan Events and Tail Risks: The Unseen Dangers

Perhaps Taleb’s most famous contribution to finance is his discussion of Black Swan events—rare, unexpected events that have a massive impact. These events are systematically underestimated by traditional risk models, which focus on "normal" conditions and ignore extreme outliers.

Example: Think of the 2008 financial crisis. Before the crash, most financial models based on historical data suggested that such a collapse was highly unlikely. However, the crisis did happen, and its effects were far-reaching. Taleb argues that these tail risks—events at the far ends of the probability spectrum—are what really drive market outcomes, not the more common, day-to-day fluctuations.

Mathematical Breakdown: Imagine you’re a trader who loses $1 every day betting on small market movements, but once every five years, you make $1,000 during a major crash. The expected value of this strategy could be highly positive, even though you lose money most of the time:

Expected return=(−1×364)+(1000×1)=−364+1000=+636

In this scenario, the Black Swan event (the rare market crash) more than compensates for the daily losses, illustrating Taleb’s belief that rare, extreme events are underpriced by markets. Betting on these tail events can lead to outsized returns, but it requires extreme patience and discipline.

7. Risk and Asymmetry: Thinking Beyond Probabilities

Taleb argues that most investors and traders fail to grasp the importance of asymmetry in outcomes. It’s not just about how often you win but the magnitude of wins and losses. A strategy that wins 90% of the time but loses big 10% of the time can be worse than one that wins infrequently but avoids large losses.

Example (Options Trading): Imagine you buy a call option for $1, giving you the right to buy a stock at $110. If the stock goes up to $120, you can sell it for a $9 profit ($120 - $110 - $1 premium). But if the stock doesn’t rise above $110, you lose only your $1 investment. This illustrates asymmetry—your losses are capped, but your potential gains are much larger.

Taleb encourages investors to seek out opportunities with this kind of asymmetry: where the downside is limited, but the upside is substantial. In his trading strategy, he regularly took small losses while positioning himself for rare, large gains.

8. Law of Large Numbers: The Long-Term Triumph of Averages

Finally, Taleb touches on the law of large numbers, which states that as the number of observations increases, the average of the results tends to converge on the expected value. However, this doesn’t mean short-term results will always reflect long-term trends.

Example: Consider flipping a coin. In the short term, you might see a streak of 10 heads in a row. But over 1,000 flips, the ratio of heads to tails will converge towards 50/50. The same applies to markets—short-term fluctuations can be misleading, but over the long run, averages tend to smooth out.

Taleb’s lesson here is to not overreact to short-term noise and randomness. While markets may behave erratically over short periods, the law of large numbers ensures that long-term outcomes will be more predictable, albeit still subject to rare Black Swan events.

Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness is a profound reminder that randomness dominates more aspects of life and markets than we care to admit. By understanding the nuances of probability, expected value, and tail risk, investors can make better decisions, avoid common psychological traps, and prepare for the unpredictable.